Breaking Barriers: A Thought-Provoking Analysis of Robert Frost’s Mending Wall

Robert Frost’s Mending Wall, An Introduction

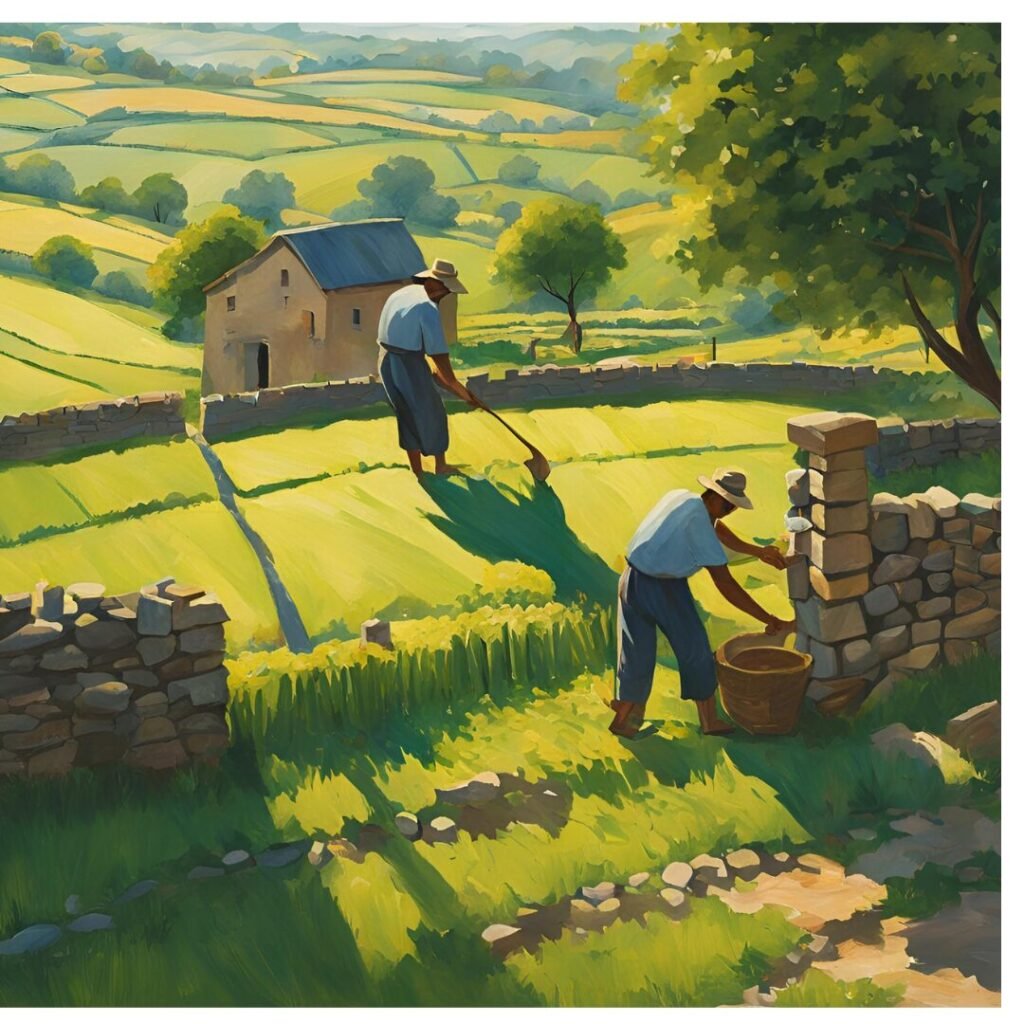

Robert Frost‘s Mending Wall is a compelling exploration of human relationships, boundaries, and the paradox of separation and connection. Written in 1914, the poem is part of Frost’s second collection, North of Boston, and remains one of his most celebrated works. Through its vivid imagery, conversational tone, and philosophical undertones, Mending Wall invites readers to reflect on the necessity and impact of the barriers we build, both physically and emotionally.

Setting the Scene: The Annual Ritual

The poem begins with the line, “Something there is that doesn’t love a wall,” immediately setting the stage for a meditation on the natural world’s resistance to man-made barriers. The narrator describes the annual ritual of repairing a stone wall that separates his property from his neighbor’s. Despite the wall’s persistent decay due to natural forces like frost and the shifting ground, the neighbor insists on rebuilding it, adhering to the adage, “Good fences make good neighbors.”

This ritualistic mending becomes more than just a physical activity; it symbolizes the human tendency to maintain divisions even when they no longer serve a clear purpose. The narrator questions the need for the wall, especially since there are no livestock to contain—only apple trees on one side and pine trees on the other. Yet, the neighbor remains steadfast, embodying the unexamined adherence to tradition.

Themes of Tradition vs. Change

At its core, Robert Frost’s Mending Wall examines the conflict between tradition and change. The neighbor represents the conservative mindset that values established customs without questioning their relevance. His reliance on the proverb reflects a broader societal inclination to uphold boundaries simply because they have always existed.

In contrast, the narrator adopts a more inquisitive stance, challenging the necessity of the wall. He muses on the absurdity of maintaining a barrier that nature itself seems eager to dismantle. This dynamic creates a subtle tension between the comfort of familiarity and the potential for growth through questioning and adaptation.

Nature’s Role: A Silent Protest

Frost masterfully uses nature as a silent character in the poem, subtly protesting against the wall. The natural forces that cause the wall to crumble symbolize the inherent desire for openness and connection. The gaps that “even two can pass abreast” suggest that the world does not naturally conform to human-imposed separations.

The narrator notes, “We do not need the wall,” highlighting the idea that boundaries are often artificial constructs, maintained out of habit rather than necessity. Nature’s quiet rebellion against these barriers serves as a metaphor for the futility of resisting change and the natural inclination toward unity.

The Irony of Separation in Robert Frost’s Mending Wall

One of the poem’s most striking features is its ironic portrayal of the wall as both a divider and a point of connection. The annual task of repairing the wall brings the two neighbors together, creating an interaction that might not occur otherwise. In this sense, the wall functions paradoxically: it separates, yet also unites.

This irony in Robert Frost’s Mending Wall extends to the broader human experience. People often build emotional walls to protect themselves, only to find that these barriers can isolate them from meaningful relationships. Frost subtly critiques this tendency, suggesting that true connection comes not from maintaining walls but from the willingness to question and, when necessary, dismantle them.

The Neighbor as a Symbol

The neighbor in Robert Frost’s Mending Wall is more than just a character; he represents a universal archetype—the person who clings to tradition without reflection. His repetition of “Good fences make good neighbors” underscores his resistance to change and his reliance on inherited wisdom. He is described as moving “in darkness,” not just in the literal sense of shadow but metaphorically, indicating ignorance or an unwillingness to see beyond the familiar.

In contrast, the narrator embodies a more enlightened perspective, challenging outdated beliefs and advocating for introspection. Through this juxtaposition, Frost encourages readers to examine their own tendencies to accept norms without question.

Language and Structure: Conversational Yet Profound

Frost’s use of blank verse lends the poem a natural, conversational rhythm, making its philosophical musings accessible and engaging. The colloquial language contrasts with the depth of the themes, creating a sense of intimacy and authenticity. The poem’s structure, with its flowing lines and lack of formal stanzas, mirrors the organic, uneven nature of both the wall and the ideas it explores.

The repetition of key phrases, such as “Something there is that doesn’t love a wall” and “Good fences make good neighbors,” reinforces the central conflict and highlights the persistence of both natural forces and human beliefs. Frost’s choice of simple yet evocative imagery—stone walls, pine trees, apple orchards—grounds the poem in a tangible reality, while inviting broader interpretation.

Conclusion: Beyond the Wall

Robert Frost’s Mending Wall is a timeless reflection on the human condition, exploring the walls we build—literal and metaphorical—and the reasons we maintain them. Through the interplay of tradition and inquiry, separation and connection, Frost challenges readers to consider the purpose and consequences of their boundaries.

Ultimately, the poem suggests that while walls may offer a sense of security, they can also hinder growth and understanding. By questioning the need for such barriers, we open ourselves to deeper connections and a more profound appreciation of the forces that unite us. Frost’s work remains relevant, urging us to look beyond the walls we inherit and to embrace the possibilities that lie beyond.

Something there is that doesn’t love a wall,

Something there is that doesn’t love a wall,

That sends the frozen-ground-swell under it,

And spills the upper boulders in the sun;

And makes gaps even two can pass abreast.

The work of hunters is another thing:

I have come after them and made repair

Where they have left not one stone on a stone,

But they would have the rabbit out of hiding,

To please the yelping dogs. The gaps I mean,

No one has seen them made or heard them made,

But at spring mending-time we find them there.

I let my neighbor know beyond the hill;

And on a day we meet to walk the line

And set the wall between us once again.

We keep the wall between us as we go.

To each the boulders that have fallen to each.

And some are loaves and some so nearly balls

We have to use a spell to make them balance:

‘Stay where you are until our backs are turned!’

We wear our fingers rough with handling them.

Oh, just another kind of out-door game,

One on a side. It comes to little more:

There where it is we do not need the wall:

He is all pine and I am apple orchard.

My apple trees will never get across

And eat the cones under his pines, I tell him.

He only says, ‘Good fences make good neighbors.’

Spring is the mischief in me, and I wonder

If I could put a notion in his head:

‘Why do they make good neighbors? Isn’t it

Where there are cows? But here there are no cows.

Before I built a wall I’d ask to know

What I was walling in or walling out,

And to whom I was like to give offense.

That wants it down.’ I could say ‘Elves’ to him,

But it’s not elves exactly, and I’d rather

He said it for himself. I see him there

Bringing a stone grasped firmly by the top

In each hand, like an old-stone savage armed.

He moves in darkness as it seems to me,

Not of woods only and the shade of trees.

He will not go behind his father’s saying,

And he likes having thought of it so well

He says again, ‘Good fences make good neighbors.’